| Return to the previous page |

Content↑ | Next Page |

28-1. Follow the Immense River, the Amazon

Part 1: Peruvian Amazon

Uploaded on February 22, 2025

When you click or tap on a photo or diagram, a larger image will pop up. Return with ✕ in the bottom right.

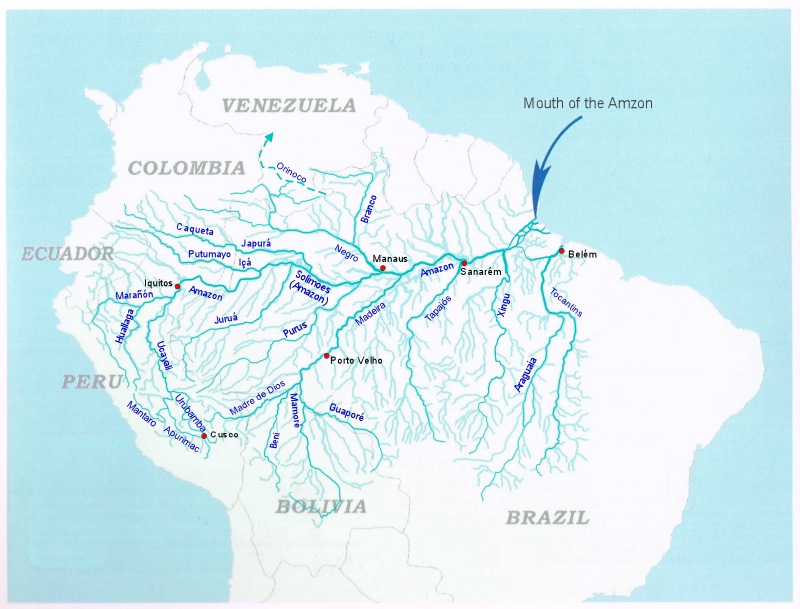

Drainage Network of the Amazon River

The Amazon River, which is not as long as the Nile in Africa and may even lose to the Yangtze, is by far the largest river in the world in terms of basin area and discharge. The uppermost part of the river flows through the valley of the rugged Andes mountains, then into the flat lowlands, and flows through meandering channels that changes shape from moment to moment. In the middle stream it flows through a remarkably deep channel, and finally flows in the estuary (triangular river mouth) scattered with large and small islands to flow into the Atlantic Ocean. We will trace this great river that flows down while changing its character, from upstream to downstream.

About this map of drainage network: Based on the drainage net chart by M. Goulding et al. (2003) "The Smithsonian Atlas of the Amazon (Smithsonian Books) p.101", it was created by emphasizing major rivers and supplementing major city and place names. In addition, the upper reaches of the Orinoco River, where part of the flowing water diverts to the Casiquiare River in the upper reaches of the Negro River, were added with a dashed line.

| PanoraGeo Contnt↑ | Next Page↓ |

| Follow the Amazon River | 1 /21 | Previous Page | Next Page |

Marañón River flowing through the Andes

South of Iquitos, a city in northeastern Peru, two large tributaries merge to form the Amazon River. One is the Ucayali River and the other is the Marañón River.

The upper reaches of the Marañón River flow north through a longitudinal valley (a valley parallel to the direction of the mountain range) that separates the Western Mountain Range (West Cordillera) and the Central Mountain Range (Central Cordillera) of the Andes. The photo is looking downstream from the hillside on the right bank of this river valley (elevation 3,450 m). The elevation of the valley floor is 3,100 m, and the peaks of the mountains in the vicinity, including the mountains seen in the distance, are about 4,200 m. As the region is located in the densely populated Quechua and Suni zones in the geographical altitude zone of the Peruvian Andes, the valley slopes from the valley floor to an altitude of nearly 4,000 m are fully cultivated.

70~80km upstream is Lake Lauricocha, the source of the Marañón River and once thought to be the source of the Amazon River.

Photographed on July 28, 1986 Camera position; (Latitude and Longitude):-9 51 8.40, -76 36 56.74 (Google Map) Shooting direction: 305°clockwise from north

PanoraGeo-No.399

| Previous Page | Next Page |

| Follow the Amazon River | 2 /21 | Previous Page | Next Page |

Nevado Salcantay (or Mt. Salkantay), a famous peak in the Andes in the upper reaches of the Ucayali River

The Ucayali River is another major tributary of the upper Amazon along with the Marañón. The Ucayali River flows for about 1,500 km along the eastern foothills of the Andes through a lowland covered with tropical rainforest. Its upper reaches are made up of two major tributaries that flow through the Andes: the Apurimac and the Urubamba. In this photo, Mount Salkantay rises above the watershed of these two rivers, which flow through a deep valley in the Vilcanota Massif of the Eastern Mountain Range of Andes.

The southern face of Mt. Salkantay (in the foreground of the photo) is the river basin of the Apurimac, and on the other side is the deep valley of the Urubamba. Near the northern end of the ridge that stretches towards the Urubamba River is Machu Picchu, a tourist destination famous for its Inca ruins. At 6,271 m above sea level (according to some estimates, 6,264 m), Mt. Salcantay is the 14th highest mountain in Peru, but its prominence, which indicates the degree of protrusion from its surroundings, is 2,540 m, second only to the 2,776 m of Mount Huascarán (6,768 m), Peru's highest peak, indicating that it is not an easy mountain to climb.

Until now, the "headwaters of the Amazon River" (the starting point of the longest channel of the Amazon system) have been considered to be located in the upper reaches of the Apurimac River in southern Peru. However, in recent years, the view that the source of the Amazon River is far away in the upper reaches of the Mantaro River in central Peru has come to the forefront, and it has attracted attention in some quarters*1) (see:Where does the Amazon River come from? Part 1).

*1) For example, CNN travel (Updated on October 2, 2023): What’s the world’s longest river? New expedition aims to settle the debate once and for all.

Photographed on September 15, 2011 Camera position; (Latitude and Longitude):-13 25 31.34, -72 30 40.11 (Google Map) Shooting direction:333°clockwise from north

PanoraGeo-No.238

| Previous Page | Next Page |

| Follow the Amazon River | 3 /21 | Previous Page | Next Page |

Upper Mantaro River Basin in the Andes Mountains

This is a view of the Andes Mountains in the north direction from the window of an airplane from Lima to Iquitos. In the distance near the upper left corner of the photo, there is the Cordillera Blanca, where Peru's highest peak, Nevado Huascarán (6,768 m), is located, and near the left edge, the white peak of Yerupajá (6,635 m), Peru's second highest peak, looks slightly larger. These mountains of the Western Andean Cordillera are the watershed of rivers that flow west into the Pacific Ocean and rivers that flow east into the Amazon River.

The area in this photograph east of this mountain range is the headwaters of the Mantaro River, a tributary of the upper Amazon River. Measurements using Google Earth satellite imagery confirm that the headwaters of the Amazon River (the farthest point along the path from the mouth of the river) are located in this area.

The small flat area in the upper part of the photo is the 4,100-meter-high Meseta de Bombón Plateau, the southern part of which is occupied by Lake Junín (also known as Laguna Chinchaycocha), the second largest lake in Peru after Lake Titicaca. The source of the Amazon River must be somewhere in the Meseta de Bombón Plateau or in the mountains surrounding it (see:Where does the Amazon River come from? Part 2).

Photographed on July 9, 1981 Camera position; (Latitude and Longitude):-11 34 16.19, -76 14 21.90 (Google Map) Shooting direction:335°clockwise from north

PanoraGeo-No.738

| Previous Page | Next Page ↓ |

| Follow the Amazon River | 4 /21 | Previous Page | Next Page |

Mountains east of Junín City, where the headwaters of the Amazon are located

Looking east from Junín, a town south of Lake Junín, there are several rocky peaks beyond rolling hills covered with highland grasslands. The high peaks of Central Cordillera of the Andes lying east of the Bombón Plateau do not appear so high from the Junín Plain *1) at an altitude of 4,100 m. The high mountain in the photo is Cerro Rispanga, a rocky peak at an altitude of 4600m. The Mt. Chipián (4,751 m above sea level), which PanoraGeo recognizes as the source of the Amazon River, is also such a rocky peak. Mt. Chipián rises over the rolling hills that continue outside the right frame of this photo. (See:Mt. Chipián, the source point of the Amazon River, seen on Google Street View. )。

The gentle hills in the foreground are moraines left behind by glaciers that flowed from these high peaks during the glacial period, and are made up of gravel and rock masses of various sizes. In some places, large rock masses are exposed in the ichu grass meadows that cover the hills. This highland grassland, which corresponds to the Puna zone in the geographical altitude zone of the Peruvian Andes, was mainly grazing, but potatoes were also grown in nearby fields.

*1) Pampa de Junín is part of the Bombón Plateau, a plain that stretches southeast of Lake Junín. In 1824, the Battle of Junín, which decisive the victory of the Peruvian War of Independence, was fought, and the Chacamarca Obelisk commemorates this battle.

Photographed on July 27, 1986 Camera position; (Latitude and Longitude):-11 9 50.10, -75 59 20.12 (Google Map) Shooting direction: 55°clockwise from north

PanoraGeo-No.739

| Previous Page | Next Page ↓ |

| Follow the Amazon River | 5 /21 | Previous Page | Next Page |

Remarkable meandering river, the Ucayali

The eastern foothills of the Andes Mountains, where the Ucayali River, one of the two major tributaries of the upper Amazon River, flow, are geologically called the anterior basin of the Andes, and geographically called the central lowlands of the South American continent. Due to the extremely flat land that is still sinking, the Ucayali River meanders and diverts to the right and left through a wide floodplain. Since the entire section is a prominent meandering river as shown in this photo, the actual length of the channel is about twice as long as if there were no meanders.

The section called the Ucayali River runs from the town of Atalaya at the confluence of the Tambo River (the lowest part of the Apurimac and Mantaro rivers system) and the Urubamba River flowing down from the Andes to the confluence of the Marañón River, and is about 1,500 km long. However, meandering rivers such as the Ucayali River are particularly subject to severe movement and deformation of its channel, and their lengths are constantly changing (See: Sevear movement and deformation of the channel of the Ucayali River. For example, if a shortcut (cut-off) occurs in the constricted part of the large meander as in the foreground of the photo, the length of the channel will be shortened by more than 10 km in one fell swoop. Using the 1998 Google Earth satellite image, the length of the Ucayali River was 1,564 km, but in 2019 it was 1,549 km, and in 2024 it was 1,534 km.

Therefore, the length of the entire Amazon River is also not constant, and it makes no sense to give a clear figure. In the future, it may be expressed in the form of 30-year normal values, such as temperature and precipitation, but for now, one way is to add the year of acquisition of the image or the year of survey of the measured material, such as "Amazon River: 6,286 km (2024)".

Photographed on June 29, 1981

Camera position; (Latitude and Longitude):-5 53 26.22, -74 24 6.66 (Google Map)

Shooting direction:253°clockwise from north

Center of the photo image:-6 2 0.66, -74 53 3.86 (Google Map)

PanoraGeo-No.400

| Previous Page | Next Page ↓ |

| Follow the Amazon River | 6 /21 | Previous Page | Next Page |

Ucayali River and two types of tributaries

The thick river seen in the upper left corner of the photo is the Ucayali River, which flows in the rainforest of the Amazon Plain, with the left side of the photo being upstream and the upper side being downstream. In the upper left part of photo, the bend of the meandering has progressed considerably, and the upstream and downstream channels are quite close. This part is called the neck of the meandering channel, and when the bend progresses further, the cut-off of the channel occurs here, and the original channel becomes a crescent lake as a meander scar.

Two tributaries join the main stream of the Ucayali River from the bottom of the photo. The right tributary, which has a whitish color, is finely meandering. The wavelength and amplitude of the meander are relatively small in rivers with a small width. In general, the amplitude of the meander, that is, the width of the meandering zone, is 10-25 times the width of the river. On the other hand, the other tributary on the left (the black river), which is less prominent due to the blackness of the water, is hardly meandering. Why does this difference occur?

This is related to the amount of sediment carried by the river. The amplitude of the meander gradually increases as the outside of the curve is eroded by flowing water and sediment is deposited on the inside. In this case, the erosion of the outer shore is more visible, but it is the deposition of sediment inside the bend that plays an important role. The accumulated sediment pushes outward the flow, which hits the opposite bank strongly and erodes. The white river in this photo is a turbid river that contains a large amount of sediment, so it meanders remarkably. On the other hand, rivers that transport little sediment and do not accumulate sediment in the channel, do not meander, and the river channel is stable. The black river in this photo is such a river.

How will these rivers have changed in about 30 years? (See: Changes in the course of the main and tributaries of the Ucayali River, 1981-2012) The fairly large deforested area on the right bank of the black river is probably the field or ranch of the locals who learned of this fact.

Photographed on July 9, 1981 Camera position; (Latitude and Longitude):-10 23 1.75, -73 56 6.87 (Google Map) Shooting direction:333°clockwise from north

PanoraGeo-No.30

| Previous Page | Next Page ↓ |

| Follow the Amazon River | 7 /21 | Previous Page | Next Page |

The Amazon near Iquitos in Peru (1981)

Iquitos, the capital city of the province of Loreto, in the Selva region of Peru, in the upper Amazon River, had a population of 380,000 in the 2017 census, but has grown rapidly in recent years, reaching nearly 500,000 in 2022. The photo shows the northern end of the city of Iquitos and the Amazon River flowing along it to the north (toward upper direction in the photo).

120 km upstream, two major tributaries, the Ucayali and Marañón Rivers, merge to form the Amazon River. The water of the Amazon River is brown and turbid with a large amount of sediment. However, even if it is brown, the locals call this type of river "white river". On the other hand, you can see that the color of the Nanay River, which joins from the left side of the photo, is slightly different from the Amazon River. The river is a "black river" with clear but blackish water with almost no sediment.

Over the next 20 years, the course of the Amazon River in the region will undergo a surprising change, as shown by satellite image of Iquitos and the Amazon River in 2005.

Photographed on June 27, 1981 Camera position; (Latitude and Longitude):-3 44 52.31, -73 14 34.55 (Google Map) Shooting direction:10°clockwise from north

PanoraGeo-No.222

| Previous Page | Next Page ↓ |

| Follow the Amazon River | 8 /21 | Previous Page | Next Page |

Floodplain settlements in Iquitos, Peru

In 1981, when this photo was taken, the Amazon River ran along the city of Iquitos, the capital of the Peruvian Amazon. Most of Iquitos' urban area is on uplands (river terraces), but the lowlands (floodplains) in the south are also home to the poor. In this photo, the place where countless houses are gathered in the distance is such a floodplain settlement. Both the place where the house is located and the water surface to the left of it are the floodplains of the Amazon River. In June, when the photo was taken, the water level of the Amazon River was high, so the floodplain was immersed in the brown and turbid water of the Amazon. Many houses in the floodplain are floating houses prepared for such inundation during high water periods.

Subsequently, a major change in course occurred, and the Amazon River ceased to flow along the city of Iquitos, leaving a lake along the city. The Itaya River, which flows into the lake, is not a muddy brown river like the Amazon, but a river that is transparent but darkened, or "black river". Therefore, the lake facing the city of Iquitos has now turned into black water. (See:Recent large-scale changes in the course of the Amazon River near Iquitos).

Photographed on June 29, 1981 Camera position; (Latitude and Longitude):-3 44 34.78, -73 14 26.29 (Google Map) Shooting direction:190°clockwise from north

PanoraGeo-No.401

| Previous Page | Next Page ↓ |

| Follow the Amazon River | 9 /21 | Previous Page | Home(index)↓ |

Iquitos floodplain settlements in the low water period

This photograph was taken in August 1986 of the floodplain and settlement of the Belém district in the southern part of the city of Iquitos, and the position and angle are almost identical to the photo on the previous page (PanoraGeo-No. 401) taken in June 1981. In the 1981 photo, all the places that used to be water have become green grasslands, and it feels like a different world. This change was caused by the seasonal difference between the 1981 photo taken in June and this photo in August, as well as the resulting change in the water level of the Amazon River.

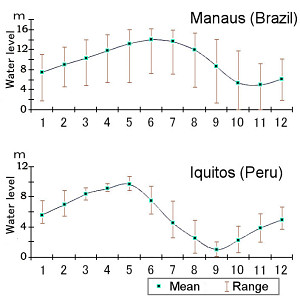

As can be seen in the graph on the right, the water level of the Amazon River drops by 4-5 m in a short period of only 2 months. The annual variation in the level of the Amazon River in Iquitos is quite large, with an average of 8.4 m, with the highest water level appearing in May and the lowest in September. The drop in water level is much more rapid than the rise. Changes in water levels in the city of Manaus in the middle Amazon have shown a similar trend, but this is even more pronounced in Iquitos.

Local farmers are most focused on cultivating the fertile floodplains. Hurry to sow various crops in June and July, when the water level drops rapidly, and the land appears one after another from under the water. Then, from September to December, when the water level slowly rises, the crops are harvested leisurely*1)

。 *1) Hiraoka, M.(1985):

Floodplain Farming in the Peruvian Amazon. Geographical Review of Japan, 58-B.

*2) Goulding, M. et al.(2003):The Smithsonian Atlas of the Amazon. p.34

Photographed on August 13, 1986 Camera position; (Latitude and Longitude):-3 45 1.18, -73 14 34.05 (Google Map) Shooting direction:190°clockwise from north

PanoraGeo-No.402

| Previous Page | Home(index)↓ | To:Follow the Amazon River Part 2: Brazilian Amazon

Uploaded on February 22, 2025